From my theological perspective, the outside ring, the ultimate goal, the topic encompassing everything, is kedusha, holiness. For me, my ultimate purpose, the reason for my creation, is to serve God, or, in the Ramban’s words, “to cling to the Holy God, as it is written in Kedoshim, “You should be holy because I Am holy.” I don’t expect that to work for everyone. But I do wonder whether, if others understand kedusha not as “holiness,” but as “sacred purpose,” some would agree that “sacred purpose” is the ultimate goal – otherwise, what is community for?

If kedusha is the end point, I would think that the starting point is kehillah, community. In reality, kehillah being the starting point does not mean that it’s easy. You don’t become a community just because you call yourself one; community takes a lot of work and constant vigilance. But it still is the starting point. If community is us, we’re what we’ve got. And, from the standpoint of organizations, it makes sense to think in terms of “first who, then what.” From a theological standpoint, community is our power – “In the multitude of people is the King’s glory” (Proverbs 14:28). God’s glory and our power manifests in our multitudes.

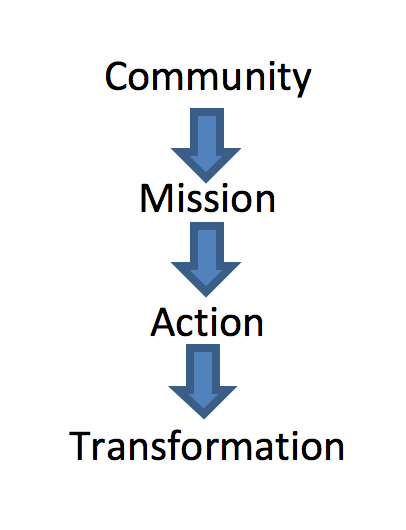

From an organizing perspective, this also makes sense. One way to think about our trajectory is:

The kehillah identifies its mission and acts on it through chochma, tzedek, and yetzira. We act as a community, and strive for sacred purpose, through learning, through justice, and through creativity. All three are things that can be done by an individual, but are so much richer, so much more lasting, so much more true when done by a community.

Chochma, wisdom, or learning, is how we strive to understand who we are as a people and what God wants of us. Without chochma, we have no history, no direction. And chochma is achieved collectively – when two people sit down and learn together; it’s as if the shechina is resting with them.

Tzedek, justice, is one way we demonstrate that community isn’t just something nice and enjoyable and that wisdom isn’t just words. One way we engage in imitatio Dei, “walking in God’s ways”, is to strive, to our limited ability, to imitate God, and a key way we do that is by relating to all the people around us as God would want us to and working to craft the world to look as God would want it to look. That can’t just happen by talking about it – it requires action.

One midrash states that God created the world multiple times before God settled on our world. This is not to claim that that actually happened, it’s to teach us various things. One thing is to teach that God creates and recreates, and so should we. If chochma teaches us who we are and who we should be, and tzedek calls on us to act on the world around us based on who we should be, yetzira, creativity, adds the art, thoughtfulness, mindfulness to our work. Kehillah, chochma, and tzedek could exist without yetzira, but they’d be far less engaging or interesting, and therefore less lasting or meaningful.

While we start with kehillah and then move into chochma, tzedek, and yetzirah, once we start on that path, the four exist in dynamic relationship with each other, each always feeding into and impacting the others. The more a community learns, acts, and creates, the stronger and more vibrant it will be. Our wisdom is deeper if it’s learned in community, as opposed to sitting alone with a book or on line. It is more nuanced if we take a creative lens to it and we prove we believe it when we don’t just talk about it but we act on it. Justice is real and impactful if it’s done by a community, as opposed to an individual, and it is much stronger if it is informed by our wisdom and nuanced by our creativity. Creativity by itself can be beautiful and compelling, but, for it to manifest into reality, it needs to happen in community and influence wisdom and action. Once the cycle begins, all four regularly swarm around each other. A community that neglects those next steps is unlikely to last long. And any of those three “next steps,” isolated from the community and the others, will be far from its full potential.

If we truly invest into the dynamism of those four categories interacting and bouncing off of each other, there will be moments where it truly feels as if we are living up to our sacred purpose. It will only be a moment – we are mortal and fallible. The Rock’s work is perfect, ours’ is not. After that moment, we will return to striving for holiness, for sacred purpose. But that moment will be enough to charge us and keep us moving forward, in community, striving for kedusha.

I could argue that God, in Exodus, telegraphed four of our categories, when God instructed Moses:

וְאַתֶּ֧ם תִּהְיוּ־לִ֛י מַמְלֶ֥כֶת כֹּהֲנִ֖ים וְג֣וֹי קָד֑וֹשׁ

“And you will be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exodus 19:6). I associate the kingdom with tzedek. A medieval rabbinic/kabbalistic commentator, the Or HaChayim, interprets the verse saying the Kingdom’s responsibility is to care for people and help them as Moses did for the Jews leaving Egypt. The priests are the repository of chochma, of our tradition, text, and history. The nation is our kehillah. And holiness, obviously, is our kedusha. We can’t settle for our niche. We need all of them to even begin to live up to our calling. How on earth could we allow ourselves to expect less of ourselves?